In this blog post series, I am documenting the development process of an implant, which can be used in adversary simulation tests aka red team operations.

Our implant will load a signed driver to execute ring-0 code and hook, bypass, or simply kill the AV/EDR. When drivers are cross-signed by Microsoft, they should be inherently trusted by security solutions and since the drivers run with kernel-level privileges, we would be able to bypass behavior-based detections and kernel callback hooking. We will also take a look at how we can interrupt or forge telemetry, how PPL can be accessed via memory operations and how we can deal with VBS.

Throughout the development of the implant, we assume admin privileges on a compromised host, either through stolen credentials, local privilege escalation, DNS Fallback account take-overs, compromised misconfigured web applications, and so on and so forth.

I’ll publish a couple of (responsible disclosed) findings and some code and if you familiarize yourself with the concepts it should be doable to write your implant you can use in your engagements. Since most of the concepts and techniques are documented plentiful all over the internet and researched thoroughly, we will just combine the best ones and throw together some custom code we can actively use for AV/EDR evasion.

I highly suggest researching your vulnerable driver as these techniques will probably be valuable for quite some time. VBS is still early, and think about how many Windows Server 2008 and 2012 boxes are lurking around in intranets nowadays. Kernel driver-based (BYOVD) attack paths are here to stay for the foreseeable future.

So grab your HEVD or research your vulnerable driver and let’s go.

So first we will take a look and a very simplified approach to how kernel driver vulnerabilities can be identified and leveraged to execute arbitrary ring-0 privileged code on a fully patched win10 2202 system, how to bypass some of the current kernel protections, and some caveats and pitfalls one might encounter. At this point, I can not share the specific kernel driver I used for the exploitation, as this is still under an embargo due to responsible disclosure. The concepts however will apply to most kernel driver vulnerability research.

obtaining kernel drivers

First, we need some drivers to analyze. There are a gazillion Windows drivers out there, I opted to download a driver package found in the interwebs. It was almost 35 gigabytes of pure driver madness and consisted mostly of very old unsigned drivers, which are not useful for our purpose. So I hacked together a very basic Python script, to check for a valid [[windows driver signatures]] signature and if the driver loads without any other hardware attached or additional software installed. The result should be a standalone .sys file that can be loaded as a kernel driver in a Windows service on a standard Windows 10 system.

import os

import subprocess

# Set the directory containing the driver files

driver_directory = "C:\\drivers"

# Iterate over all files in the driver directory

for filename in os.listdir(driver_directory):

if filename.endswith(".sys"):

# Use the signtool utility to verify the digital signature of the file

command = ["signtool", "verify", "/pa", os.path.join(driver_directory, filename)]

result = subprocess.run(command, capture_output=True, text=True)

# If the signature is valid, start the driver as a service

if "SIGNED" in result.stdout:

service_name = os.path.splitext(filename)[0]

command = ["sc", "create", service_name, "type=kernel", "error=normal", "binPath=C:\\drivers\\" + filename]

subprocess.run(command)

print("Service created for", filename)

else:

print("Invalid signature for", filename)

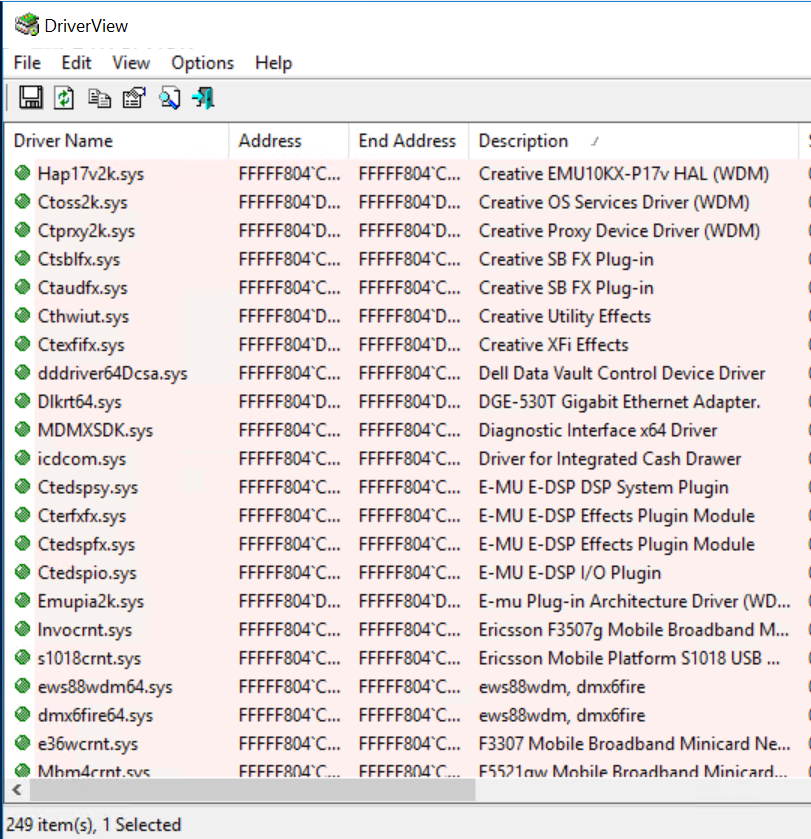

After a couple of hours and countless BSODs, I finally ended up with 249 loaded drivers.

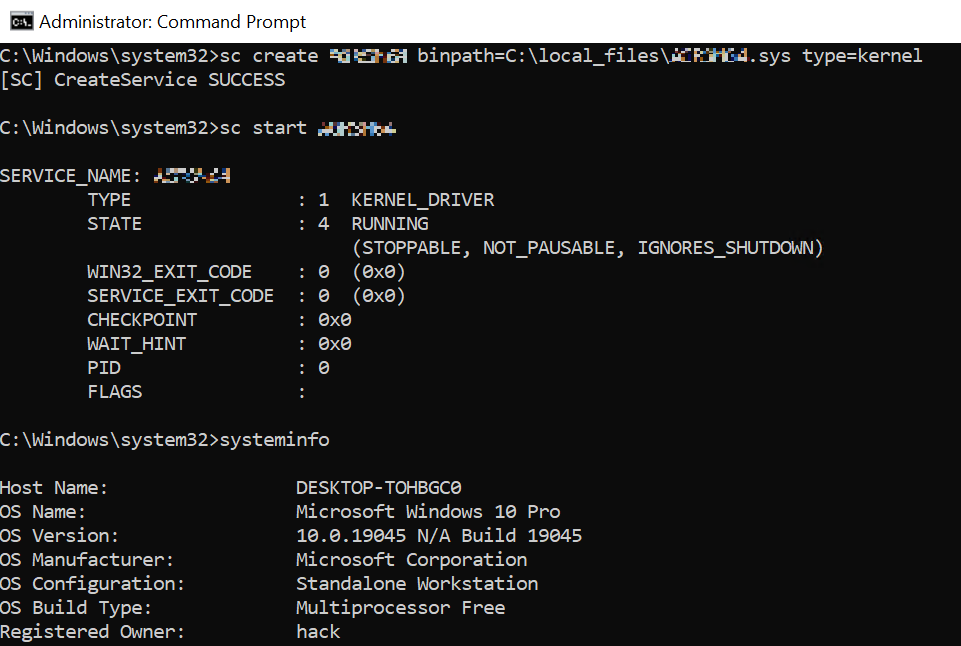

Kernel drivers are loaded via Windows service. The commands are seen below and should be self-explanatory.

choosing a target

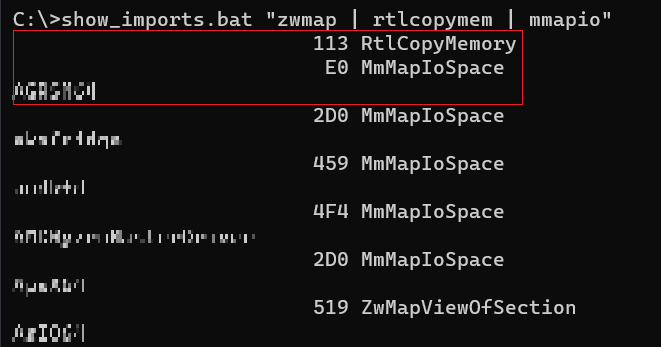

When deciding on which driver to analyze it helps to get some insights on the binary file first. We can use dumpbin to investigate the Import Address Table, and get an idea if any dangerous and potential vulnerable function calls into ntoskrnl.exe are made. Kernel drivers are usually used for interacting with hardware, that why they often implement some kind of direct memory manipulation routines. Suspicious imports include everything that copies memory like RTLCopyMemory, memcpy, memmove, and so on. Special Windows APIs such as MmMapIoSpace and friends IoAllocateMdl, MmBuildMdlForNonPagedPool and ZwMapViewOfSection usually indicate processing physical memory.

The list is far from complete as there are many logic bugs in kernel drivers, like copying between virtual memory pointers or calling some specific CPU functions like rdmsr and wrmsr. Again, you can find most of these and others worthwhile investigating online as there has been a lot of vulnerability research going on. There is even a framework for exploiting some of the bugs [https://back.engineering/22/03/2021/].

I scripted a batch file and let it run over my collection of loadable drivers:

@echo off

SETLOCAL ENABLEDELAYEDEXPANSION

for /r . %%a in (*.sys) do (

set full_path=%%a

set filename_ext=%%~nxa

set filename=%%~na

set extension=%%~xa

dumpbin /imports !filename_ext! | findstr /i /M %1

if !errorlevel!==0 (

echo !filename!

)

)

Here you can see the output of the script and some of the potential candidates.

Let’s open the first driver in Ghidra and start reversing. I applied some specific kernel API function signatures to make life easier, thanks 0x6d696368.

I’ll not go into the nitty-gritty details on how IOCTL and the IRP handling works as these are not really needed for bug hunting and there is already a lot of information about this online. The important thing is getting access to the functionalities of the kernel driver from user-mode and this is done via specific handlers calling IOCTLs.

It is maybe noteworthy that the IOCTLs themselves have some access bits set, to control who is allowed to call that specific IOCTL. you can find some details about the IOCTL struct [here]

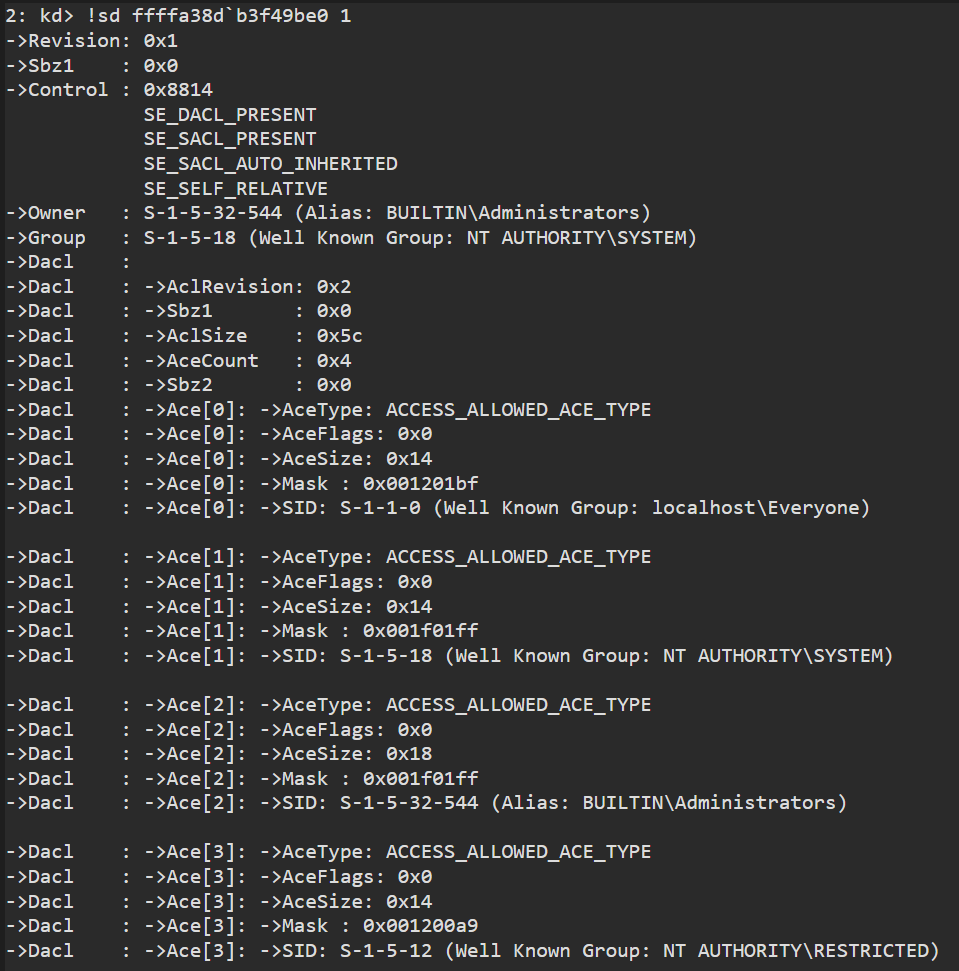

I’ll also briefly explain how you can examine the access rights your driver needs to handle IOCTLs. In case you want to responsible disclose your findings you’ll need to show impact and having a medium integrity process allowed to open a handle to the driver will get this triaged (maybe). Otherwise you probably won’t even get a reply from the vendor as most of them consider exploitation with admin rights not a vulnerability.

We can start in graph view and look for long cmp opcode chains to match the IOCTL to their handler implementation.

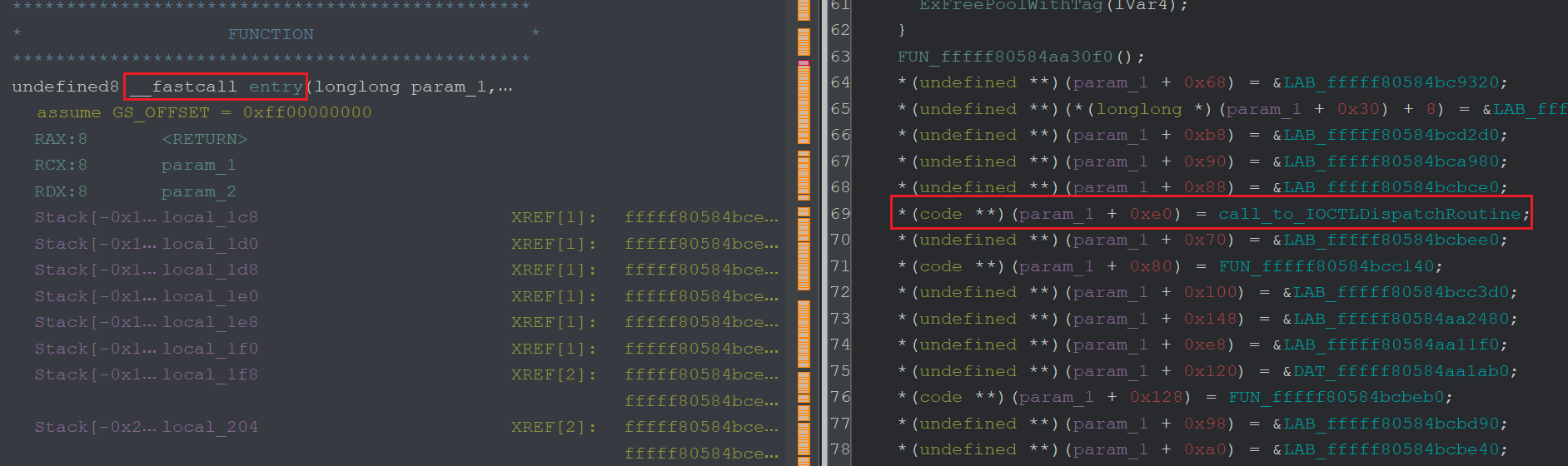

Once analyzed by Ghidra, the entry function will already be disassembled and you can select it in the function window.

I marked and renamed the most relevant function call in red, as this is where the IOCTL handlers are implemented.

To get the necessary information, specifically the offsets to where the IOCTLs are getting processed we need to fire up the kernel debugger and investigate. If you are new to kernel debugging I can recommend voidsec’s excellent tutorial on how to setup remote sessions with WinDBG.

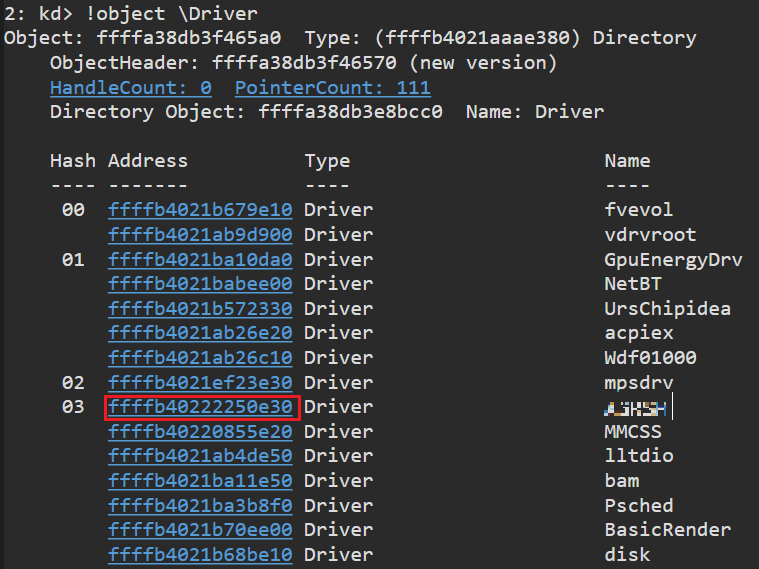

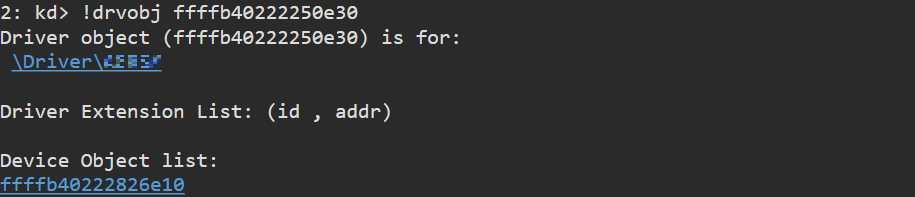

We can get our device object address:

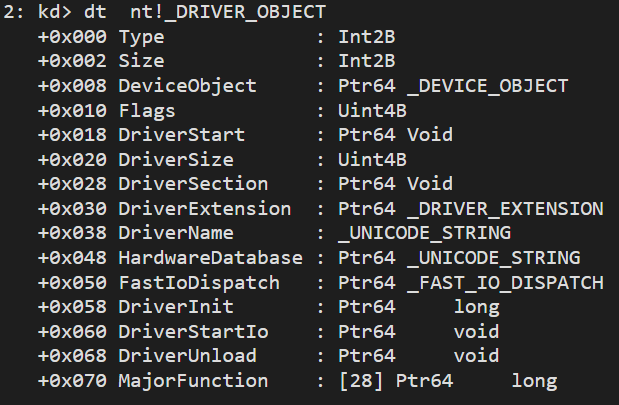

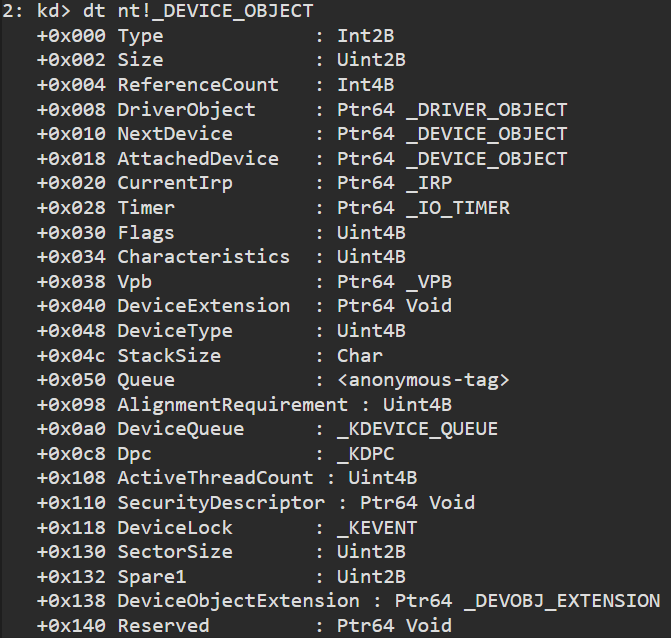

if we take a look at how the driver struct is

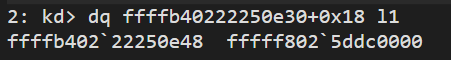

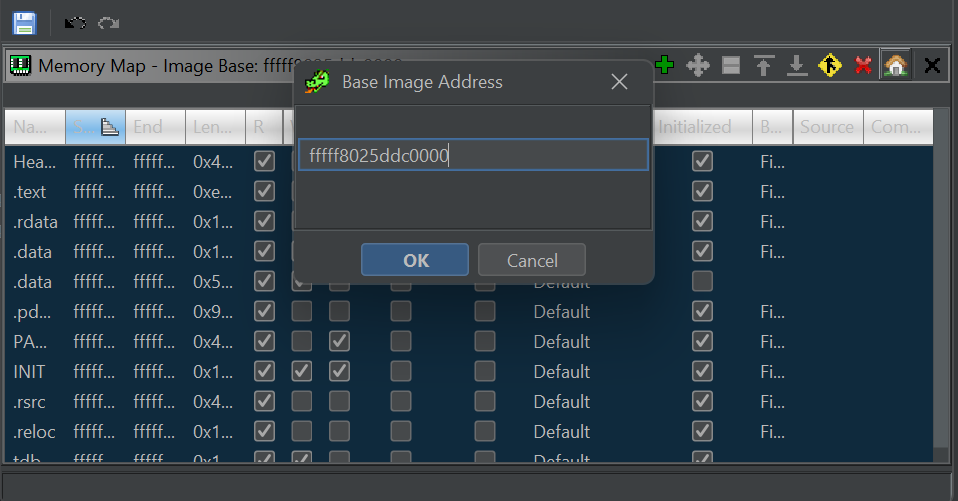

at offset +0x18 is our driver start address, we can configure Ghidra to use that offfset as base. More on that later.

we can als use the lm command to get the same informaiton, but you eed to provide the exact name of the module, which in some cases can be very different from the filename or service.

The module list start adress is the same as DriverStart

2: kd> .reload

Connected to Windows 10 19041 x64 target at (Mon Feb 13 17:26:25.413 2023 (UTC + 1:00)), ptr64 TRUE

Loading Kernel Symbols

...............................................................

................................................................

.............................................

Loading User Symbols

Loading unloaded module list

................Unable to enumerate user-mode unloaded modules, Win32 error 0n30

************* Symbol Loading Error Summary **************

Module name Error

SharedUserData No error - symbol load deferred

You can troubleshoot most symbol related issues by turning on symbol loading diagnostics (!sym noisy) and repeating the command that caused symbols to be loaded.

You should also verify that your symbol search path (.sympath) is correct.

2: kd> lm Dvm <redacted>

Browse full module list

start end module name

fffff802`5ddc0000 fffff802`5def2000 <redacted> (deferred)

Image path: \??\C:\Users\hack\Desktop\<redacted>.sys

Image name: <redacted>.sys

Browse all global symbols functions data

Timestamp: Thu Dec 3 22:05:51 2009 (4B18282F)

CheckSum: 001370DF

ImageSize: 00132000

Translations: 0000.04b0 0000.04e4 0409.04b0 0409.04e4

Information from resource tables:

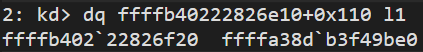

at offset 0x110 is our security descriptor address

we can see the persmissions with the command !sd

we can rebase the image in Ghidra by clicking the small memory icon in the main tool panel:

!drvobj with flag 0x02 can be used to get entry points for the driver’s dispatch routines:

2: kd> !drvobj ffffb40222250e30 2

Driver object (ffffb40222250e30) is for:

\Driver\<redacted>

DriverEntry: fffff8025deee000 <redacted>

DriverStartIo: 00000000

DriverUnload: fffff8025dee9320 <redacted>

AddDevice: fffff8025ddc2fb0 <redacted>

Dispatch routines:

[00] IRP_MJ_CREATE fffff8025deebee0 <redacted>+0x12bee0

[01] IRP_MJ_CREATE_NAMED_PIPE fffff80237f29060 nt!IopInvalidDeviceRequest

[02] IRP_MJ_CLOSE fffff8025deec140 <redacted>+0x12c140

[03] IRP_MJ_READ fffff8025deebce0 <redacted>+0x12bce0

[04] IRP_MJ_WRITE fffff8025deea980 <redacted>+0x12a980

[...]

[0e] IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL fffff8025deec750 <redacted>+0x12c750

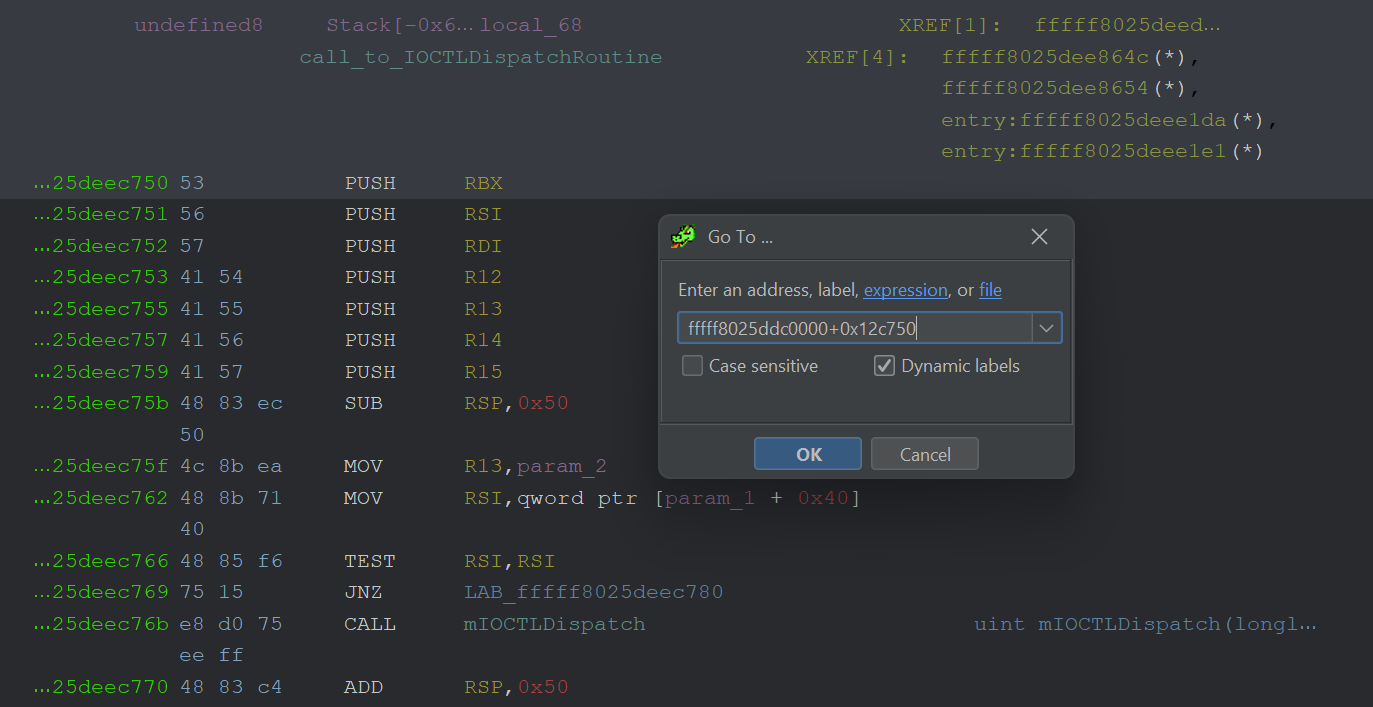

and our entry to the IOCTL Dispatch should be somewhere at offset 0x12c750

A nice IOCTL dispatch routine can be seen below:

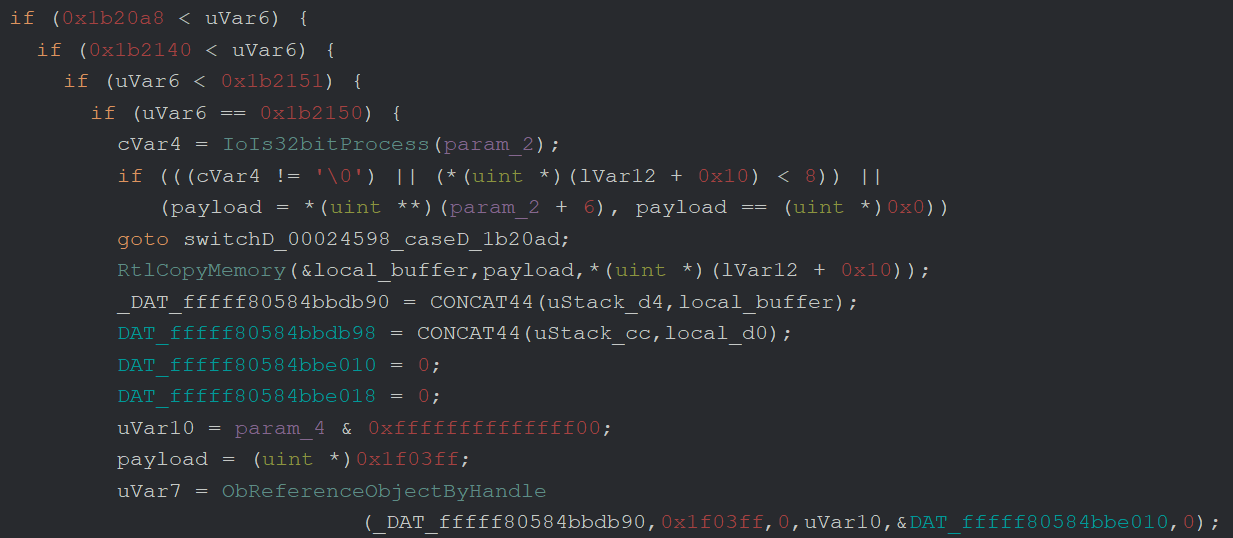

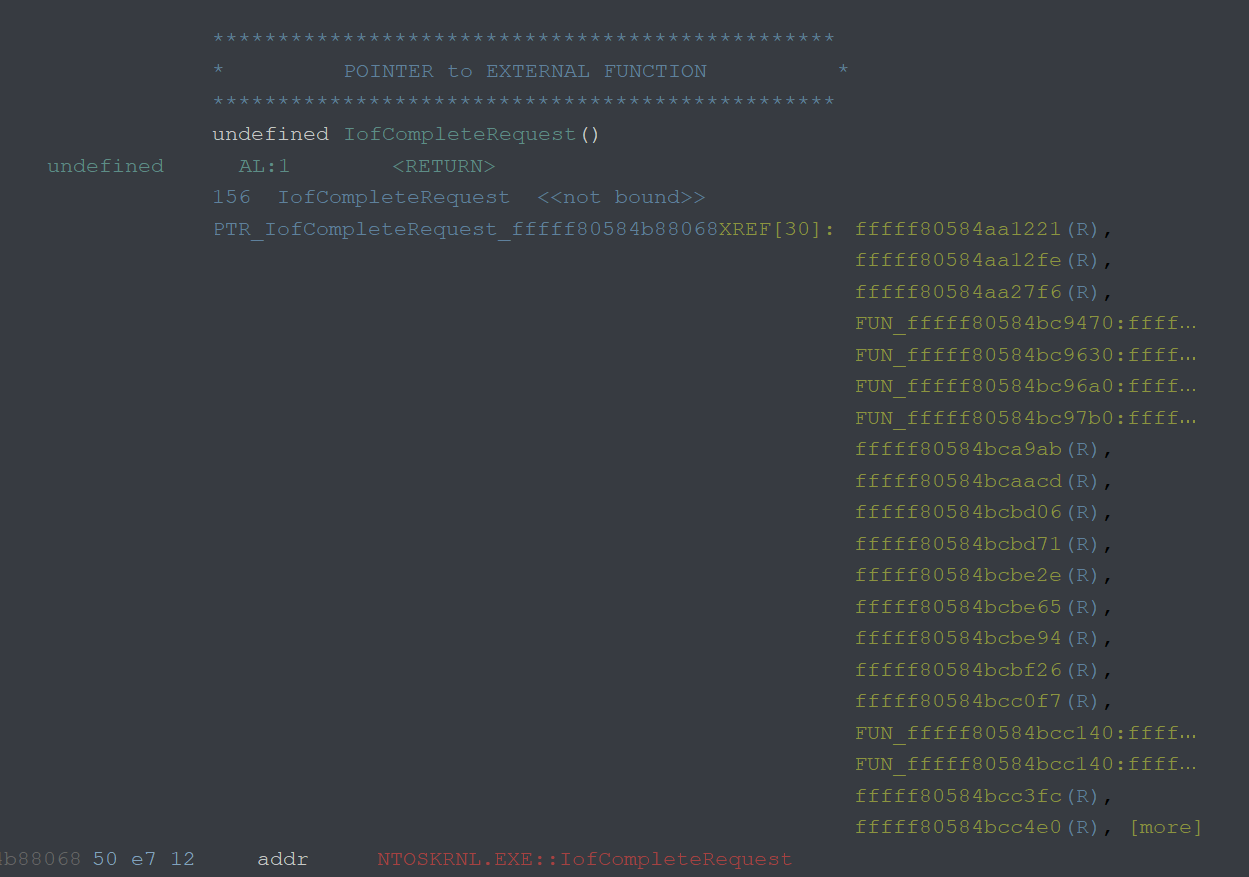

Sometimes you can save a lot of time looking for the IOCompleteRequest import from NTOSKRNL.EXE in the symbol tree, list x-references to those functions and walk backwards from there:

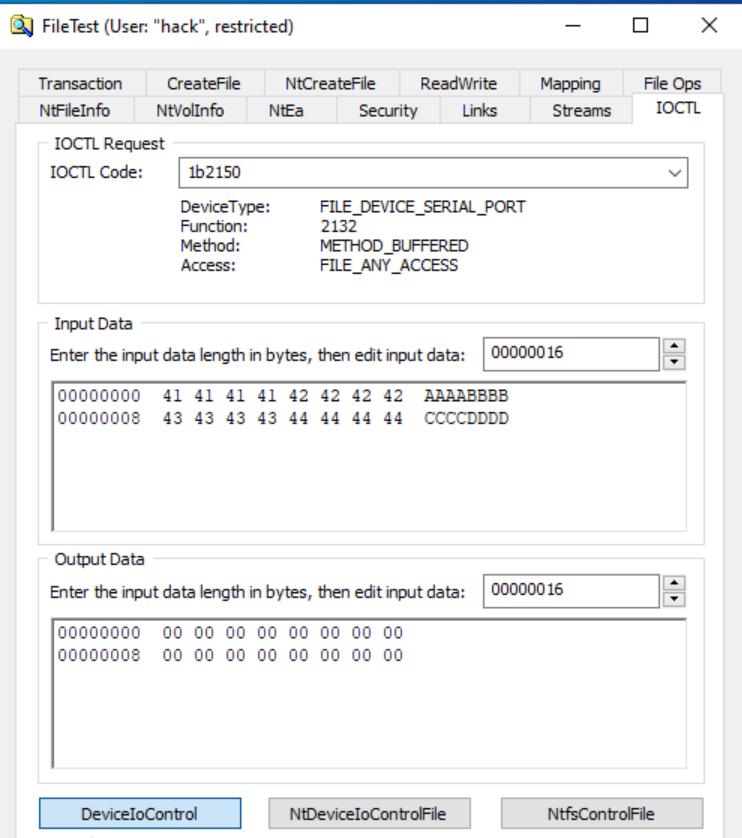

Now we are ready to inject a payload via filetest to see if our driver accepts IOCTL via user input.

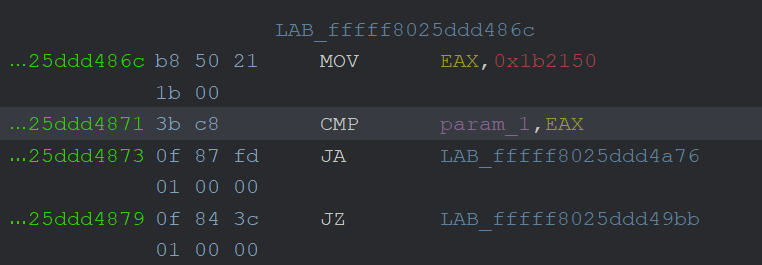

As you can see below our EAX contains the IOCTL:

0: kd> bp 0xfffff802`5dd34871

0: kd> g

Breakpoint 0 hit

<redacted>+0x14871:

fffff802`5dd34871 3bc8 cmp ecx,eax

0: kd> r

rax=00000000001b2150 rbx=ffff9c8f66e4f6b0 rcx=00000000001b2150

rdx=ffff9c8f66bfbd70 rsi=0000000000000001 rdi=ffff9c8f66bfbe40

rip=fffff8025dd34871 rsp=ffffe98266a57610 rbp=0000000000000002

r8=000000000000000e r9=ffff9c8f66e4f6b0 r10=0000000000000000

r11=ffffc97f6f800000 r12=0000000000000000 r13=0000000000000000

r14=ffff9c8f66bfbd70 r15=0000000000000000

iopl=0 nv up ei pl nz na pe nc

cs=0010 ss=0018 ds=002b es=002b fs=0053 gs=002b efl=00040202

<redacted>+0x14871:

fffff802`5dd34871 3bc8 cmp ecx,eax

Now you should be able to start your research and inject your own payloads into the kernel driver handlers from user-land. In the next post we will finally break stuff and exploit a stack-based buffer overflow in one of the drivers.